Having already given some introductory remarks regarding the book of Kings in the previous post, this post will take some of those insights further and will continue by looking in more detail at the opening chapters of Kings. I also hope to make explicit the methodology that I have been employing with the Prophetic books (as with all books among the Scriptures) in the process.

My approach to Scripture is what scholars call literary-canonical. It is literary because we focus on what the text in its finished form is doing and how it is structured. It is canonical because I want us to interpret these texts in the context of the canon of Scripture (and especially in the context of the immediately surrounding books). “Canon” is how we refer to the collection of books that make up Scripture. Paying attention to these two things – the literary features and structure AND the canonical context – will help us understand the text better. This approach takes the word of God very seriously.

This approach to Scripture leads me to emphasize two points from the start.

One is that the Book of Kings is a literary whole. It is a complete work, with a beginning and an end. One sign of this is that the book begins with the death of David (who is Jacob/Israel) and ends with the nation dead (i.e., in exile). Thus this book of Kings (and not 1 Kings by itself or 2 Kings by itself) is A BOOK. This part of the approach drives us to look inward into the text of just this particular book.

The second point to emphasize from the start stems from the fact that Kings is not alone. It is not an independent book. The immediate canonical context for Kings is that it is the final book of the former prophets (following the book of Samuel) and the book before the latter prophets (Isaiah being the next book). And this is in the context of the Torah and the Writings before and after the Prophets. This part of the approach drives us to look outward into the text of the rest of Scripture to interpret the book of Kings.

The book of Kings fits into the canonical structure of the former prophets in two basic patterns. The first is an ABA’B’ pattern where the books of Judges and Kings are alike because both begin by telling us of the death of the hero from the previous book and both show the nation descend into a downward spiral. The second is the wisdom pattern of 3+1 (usually followed by a second group of 3+1, which the latter prophets does). The +1 is the decisive punch. To put these two patterns together – if you thought Judges was bad, Kings is much worse.

So whether we are looking inwardly at the text of Kings or outwardly at the canonical context of the book – the message is loud and clear: Israel is dead. Another example of the canonical context would be to look at the book of Deuteronomy which promises blessings if the people of Israel keep Torah and curses if they fail to keep Torah. And the blessings came upon Israel (see the book of Joshua, and Samuel when David was king) but because of their failure to keep Torah the curses came upon Israel. Deuteronomy had said that the blessings would come and then the curses and the climax of those curses is the nation in exile. This theme of the death or exile of Israel is incredibly important. As early as Genesis 3 death and exile had been equated in Scripture. The story of the Old Testament is about the death and resurrection of Israel.

Also to put this book into the larger canonical context of the Hebrew Scriptures – which consists in the three parts: Torah, Prophets, and Writings – is how the prophetic book of Kings shows that wisdom (the dominant idea in the Writings) and Torah-keeping cannot save this dead nation. That is, once the nation dies, wisdom and Torah-keeping are not able to resurrect it. Solomon is the king that is most identified with wisdom and yet the nation is still dead and King Josiah kept the Torah perfectly (2 Kings 23:25) but YHWH did not turn from His wrath against Judah.

What this also means is that the nation of Israel was dead with the death of David. The path to exile was set. Torah obedience might prolong the time before exile, but it is certain to come. Once the curses begin to be poured out on Israel they will continue to be poured out until it is finished. When we get to the end of the book we should be thinking – why did God take so long? He was way too patient with Israel. But there is also the promise made to David that his son will be on the throne “forever.”

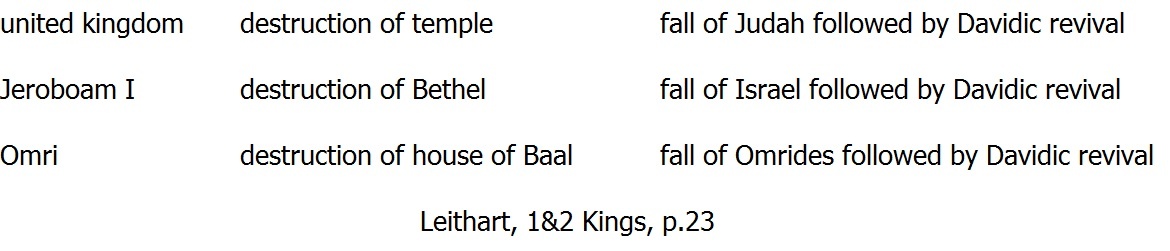

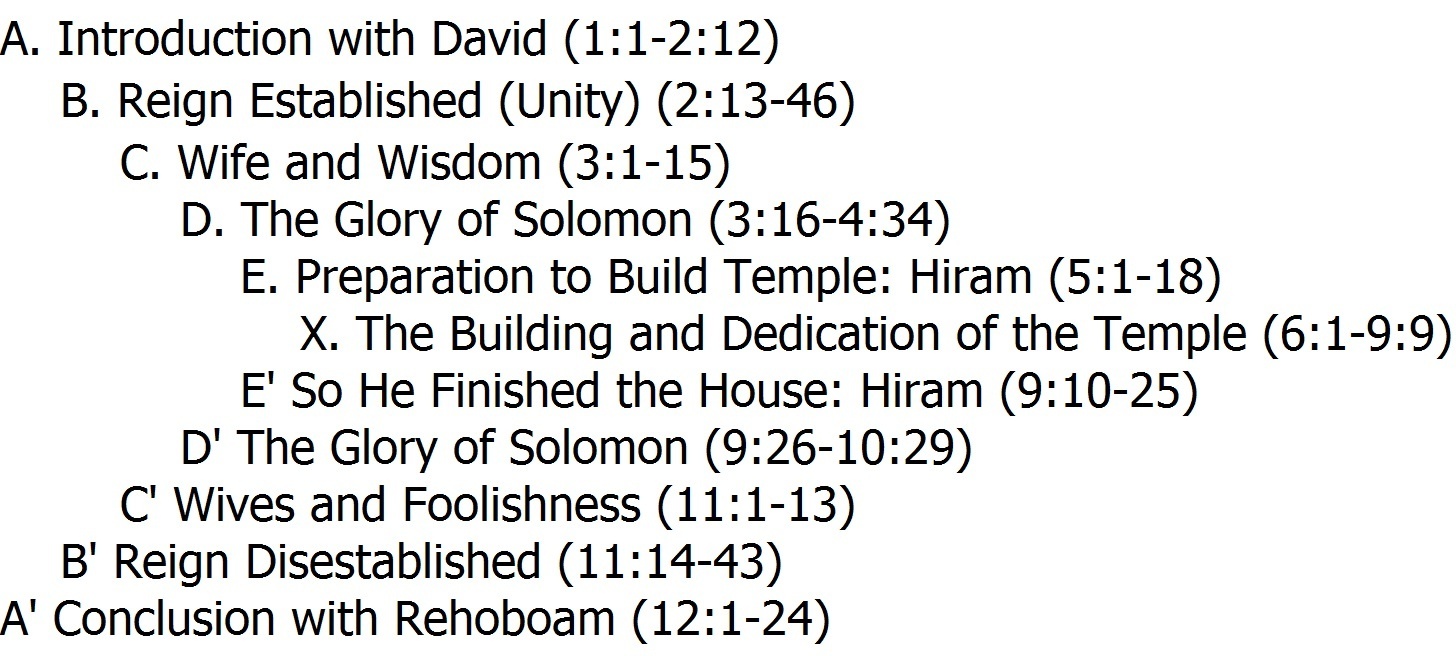

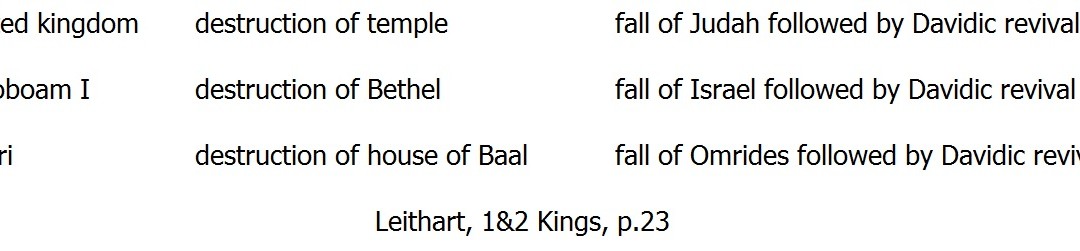

Leithart suggests this outline…we will test this as we go along to see if it is the best outline to understand the book: (note the death and resurrection pattern)

The book begins saying, “Now King David was old and advanced in years” (1 Kings 1:1).

This reminds us that David is on par with the greats of Israel’s past:

For example,

Abraham was 99 years old when he was called “old, advanced in years.” Abraham was “old, well advanced in years” when he told his servant to go find Isaac a wife. “A long time afterward…and Joshua was old and well advanced in years” (Joshua 23:1).

And…not to miss the obvious…the text begins the way that a farewell text in Scripture begins.

How fitting!

Then the problem is noted that the king is cold. And so in the verses that follow we find a beautiful young woman, Abishag the Shunammite, who is said a second time to be “very beautiful” (so that you do not miss the allusion to Bathsheba – 2 Sam 11:2 and 1 Kings 1:3-4). And the text uses the initially suggestive language: “and she was of service to the king and attended to him” but then ends “but the king knew her not.”

Why not? Was it because David is past taking additional women who pleased him? If that were the case, why not ask one of his many wives to warm him?

No, the text is pretty obvious that the reason he did not “know her” was that he was impotent. I choose this word because of the double meaning. He was unable to have sex anymore and he was powerless to do anything. Or at least that is the way others would interpret the situation. Certainly this sets the stage for Adonijah, the son of David and Haggith, to seize the throne.

To understand this passage then it was helpful to know the story of Samuel. Otherwise the force of, “and the king knew her not” might be missed by the reader. It was helpful to know that David took whatever women he found pleasing and that he would have sex with them (even if they were supposed to be off limits).

And it was helpful to know that “Now…was old and advanced in years” was a normal way of opening the setting for a farewell address in Scripture to take place.

So the text is picking right back up with the story from 1 Sam 20 (remember that chapters 21-24 where chronologically out of order). And so following the rebellion of Sheba is a new rebellion by one of his sons. It is fitting that it begins, “Now Adonijah the son of Haggith exalted himself…” (1 Kings 1:5). God has not lifted up Adonijah to be king, but Adonijah has assumed the role to himself. He probably figured that due to the death of some of those other elder brothers that he was the next in line for the throne. But it is not a surprise to one who studies Scripture that God often does not follow such customs.

Adonijah enlisted the support of Joab, the nephew of David who had been a loose cannon for a long time now, and Abiathar the priest. However, the text prepares us for the unfolding story by telling us that “Zadok the priest and Benaiah the son of Jehoiada and Nathan the prophet and Shimei and Rei and David’s mighty men were not with Adonijah” (1 Kings 1:8). And then Adonijah had a sacrificial ceremony and invited all of his brothers and royal officials “but he did not invite Nathan the prophet or Benaiah or the mighty men or Solomon his brother” (1 Kings 1:10).

Adonijah is the new Absalom. Both were said to be “very handsome” (2 Sam 14:25-26, 1 Kings 1:6). He is a figure like Saul rather than like his father David. Adonijah means Yah is My Lord and certainly YHWH shows that He is Lord in the story.

And duly prepared by the introduction to be thinking about Bathsheba, she appears to remind David of his oath that Solomon would sit on the throne after him. This was likely public knowledge, otherwise why would Adonijah not invite Solomon to his party? And then Nathan the prophet came and supported Bathsheba’s account of all these things. And David made it official and very public. Solomon rode on the king’s mule. Such similar ceremonies have been true for all the great men of Israel when they were about to die (like Aaron giving his robe to his son).

The second chapter resumes the theme of the farewell, saying, “When David’s time to die drew near, he commanded Solomon his son, saying, “I am about to go the way of all the earth. Be strong, and show yourself a man, and keep the charge of YHWH your God, walking in his ways and keeping his statutes, his commandments, his rules, and his testimonies, as it is written in the Torah of Moses, that you may prosper in all that you do and wherever you turn, that YHWH may establish his word that…you shall not lack a man on the throne of Israel” (1 Kings 2:2-4).

David continues to be portrayed as the new Joshua, as his farewell address said, “And now I am about to go the way of all the earth, and you know in your hearts and souls, all of you, that not one word has failed of all the good things that YHWH your God promised concerning you. All have come to pass for you; not one of them has failed” (Joshua 23:14). It is interesting that David puts the promise of God to him in the conditional: “If your sons pay close attention to their way, to walk before me in faithfulness with all their heart and with all their soul, you shall not lack a man on the throne of Israel” (2 Kings 1:4).

David’s farewell instructions to Solomon continue on through 1 Kings 2:9 and then we have the conclusion: “Then David slept with his fathers and was buried in the city of David. And the time that David reigned over Israel was forty years. He reigned seven years in Hebron and thirty-three years in Jerusalem. So Solomon sat on the throne of David his father, and his kingdom was firmly established” (1 Kings 2:10-11). This marks a section off by inclusio as 1 Kings 2:46b says, “So the kingdom was established in the hand of Solomon.”

We have just begun to look at the reign of Solomon. It is worth noting that the book of Kings does not give equal treatment to the kings it tells us about. Solomon is the king until his death and burial notice in 1 Kings 11:41-43. Like his father David, he reigned for forty years – a generation.

It could be then that the reason for beginning the book of Kings with death is to point to the hope of resurrection. Solomon’s reign certainly was one that brought hope. This fits with the theme of the proposed outline that we noted earlier.

It is worth noting that David’s instructions included dealing with people that David had failed to punish adequately. This included Shimei, who perhaps had tried to ingratiate himself with Solomon via 1 Kings 1:8, and Joab. These two, one from the north and one from the south, represent a threat to the unity of the nation under Solomon.

But then at the end of the narrative about Solomon we discover that because of Solomon’s turn away from YHWH that Solomon’s son will only reign over one tribe and the rest will be torn away and given to another.

This chiasm that I am suggesting, partially my own and partially observed by other commentators, highlights the fact that Solomon has a similar fault to David. 1 Kings 3:1 begins, “Solomon made a marriage alliance with Pharaoh king of Egypt” and in this chapter he has a dream where he prays for wisdom. 1 Kings 11:1 begins, “Now King Solomon loved many foreign women, along with the daughter of Pharaoh: Moabite, Ammonite, Edomite, Sidonian, and Hittite women…700 wives, princesses, and 300 concubines. And his wives turned away his heart.”

And so in the former section Solomon sacrificed at the great high place to YHWH. (This was before the Temple was built). And in the latter section, Solomon sacrificed at a high place for Chemosh the abomination of Moab, and for Molech the abomination of the Ammonites, on the mountain east of Jerusalem. Thus at the center of the chiasm is sacrifices at the Temple to YHWH. This is a very important theme in the book of Kings. Worship, as Deuteronomy prescribed, was to be done at the place where God would choose.

The parallel sections regarding Solomon’s glory focus on his wisdom and wealth. Since he had not asked for wealth but for wisdom, God gave him great wealth too.

The chiasm seems to hold up fairly well to comparing the sections. We will continue looking at the part of the book this chiasm covers next time.

Recent Comments