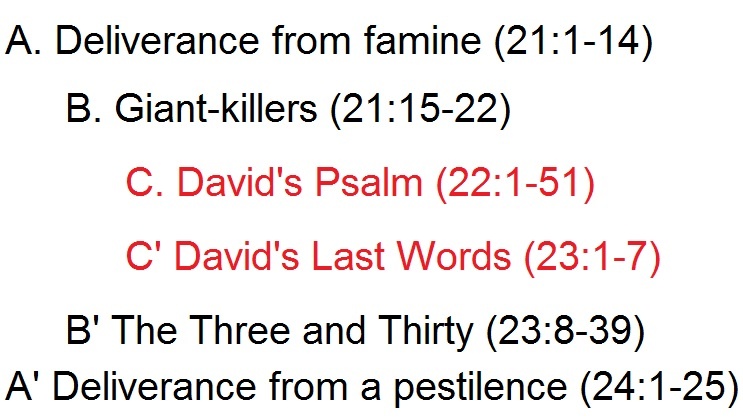

Leithart notes what he calls the “obvious chiasm” of these chapters:

There are a number of interesting correspondences within this chiasm.

2 Sam 21:1-14 and 24:1-25 are both out of chronological order – these both happened at some earlier point than the end of David’s reign.

There is a giant theme for both 2 Sam 21:15-22 and 23:8-39.

In the first section (2 Sam 21:1-14) we are reminded of the contrast between David and Saul. Saul did not keep the covenant made by Joshua with the Gibeonites. David managed to keep both the covenant Joshua made with the Gibeonites as well as the covenant that he had made with Saul’s son Jonathan. 1 Samuel left out the story of Saul’s attack on the Gibeonites. We know David avenged the Gibeonites clearly before Sheba’s Rebellion in chapter 20 though we do not know exactly when it took place. Hebrew narrative will sometimes tell things out of chronological order, especially when writing in a chiastic framework.

Saul had engaged in a holy war against the Gibeonites, contrary to the covenant Joshua made with them, trying to wholly exterminate them. Thus David rightly executed a holy war against the house of Saul (at the suggestion of the Gibeonites.)

The whole book of Samuel hinged on the death of Saul – a kind of sacrificial death that atoned for the land. The death of Absalom served the same function for the restoration of David to the throne. This chapter highlights the same principle – the death of Saul’s house atoned for the land and ended the judgment famine.

The atonement was not complete until the bones of Saul, Jonathan and the seven descendants of Saul who were put to death in this holy war were properly buried in their proper resting place. Then God sent rain to cleanse the land and responded to their prayers for fruitfulness.

The other similar story in the conclusion (2 Sam 24) regards the census that David ordered. Both stories end with the same line saying that God “responded to the plea for the land.” In both stories it was a sacrifice that removed the curse-judgment. And in both stories it was the sin of the king (in the former, Saul; in the latter, David) that led to the plague on the land. The difference between Saul and David is shown best by noting that Saul was never the kind of king who would say what David did in 2 Sam 24:17: “Behold, I have sinned, and I have done wickedly. But these sheep, what have they done? Please let your hand be against me…” David was a faithful king not because he was sinless but because he repented of his sins and interceded for his people.

This incident is related to us right after reminding us of the murder of Uriah the Hittite. He was the last of the thirty mighty men listed at the end of chapter 23. And now David called for a census, wanting to count the host of Israel – this was a military census. So we have a second sin involving the military right after the reminder of the earlier one.

Further highlighting the similarity of the episodes of Uriah the Hittite and the census is the fact that a prophet confronts David. This time it is the prophet Gad who gives him some options including three years of famine (which was the punishment mentioned in the parallel section for Saul’s holy war against the Gibeonites). He was given three options of three – three years of famine, three months of fleeing before enemies, or three days of pestilence. He chose the three days and 70,000 men of Israel died. This is the context of when David pleaded with the angel of YHWH, “Please let your hand be against me…”

The whole episode resembles the plagues of Egypt with David as the new Pharaoh. Leithart suggests because of this similarity that the sin David was committing was counting the people for his own projects. David was following in the steps of Pharaoh’s building programs. In other words, only God had the right to muster his troops but David was mustering them as if they belonged to him. David would treat Uriah the Hittites wife in a similar way – as if she belonged to him when she did not. In both situations, David acted like a Pharaoh rather than the way a Biblical king should act. Until he repented.

David did not pick the third option because it was the shortest. It was the worst option in terms of how many people would die. But the reason he chose it was, “Let us fall into the hand of YHWH, for his mercy is great; but let me not fall into the hand of man” (2 Sam 24:14). With a famine, they would have to rely on other nations for food. They would also be at the mercy (or lack thereof) of other nations if allowed to suffer from their military attacks. But this way David was dealing with God. And David would offer the sacrifice on the third day in Jerusalem (on Mt Moriah) on an altar he would build (on the site of the future Temple).

Chronologically this too almost certainly took place earlier in David’s reign. He purchased the land for the sacrifice from a Jebusite official, the situation suggesting that it was sometime relatively soon after he conquered Jerusalem.

But the reason it is recorded here is that David’s story recorded in Samuel is the story of Israel. And after the people of Israel return from exile (as we saw David do last week) there will be another numbering of the people (Ezra 2) and an altar built (Ezra 3, with the temple completed on the same site in Ezra 6).

Thus far we have looked at the A parts of the chiasm, now we will look at the two B parts.

In the first B section (2 Sam 21:15-22) we see David’s men killing descendants of the Rephaim (giants). Abishai the son of Zeruiah killed Ishbi-benob, one of these giants, “whose spear weighed three hundred shekels of bronze, and who was armed with a new sword” and wanted to kill David. Sibbecai the Hushathite killed Saph, another giant descendant. And the text tells us that Elhanan the son of Jaare-oregim, the Bethlehemite, struck down Goliath the Gittite “the shaft of whose spear was like a weaver’s beam.” But cf. 1 Chron 20:5 which may preserve the original reading (the copyist likely missed “Lahmi, the brother of”).

The fourth hero mentioned is Jonathan, the son of Shimei, David’s brother who struck down another giant from Gath – “a man of great stature, who had six fingers on each hand, and six toes on each foot, twenty-four in number…” (2 Sam 21:20) when he “taunted Israel.” The multiple of 12 is intentionally mentioned given the 12 tribes against the 24 digit giant.

These four heroes followed David’s example in giant-slaying.

The second B section (2 Sam 23:8-39) gives us a pattern of three and thirty. There were three men singled out as mighty men – Joshebbasshebeth a Tahchemonite (the leader of the three captains) who killed hundreds in one battle with his weapon, Eleazar the son of Dodo son of Ahohi who won a battle against the Philistines alone (the rest of the men of Israel had left the field), and Shammah the son of Agee the Hararite who took his stand in the midst of a plot of lentils (saving food for Israel) as the rest of the men of Israel were fleeing.

Separate from these three, the stories of which we have mentioned, is a new story about three of the thirty. David longed for water from the well of Bethlehem by the gate. And three of these thirty overheard him saying this and went and fought to get some water from the well and brought it back to him. But then David refused to drink the water and poured it out as an offering to YHWH. He realized that if he drank the water he was figuratively drinking the blood of his men. They had risked their lives to get the water, so it might as well be their blood.

The idea here is that the law prohibiting drinking blood is against the idea of men (especially kings) being bloodthirsty. He was not to send his men on personal errands in battle to satisfy his own personal desires. This was a very important lesson that David learned apparently very early on in his military exploits (though he forgot it with regard to Uriah the Hittite).

After this story about an unnamed three who were among the 30 to be named shortly, there is a story about Abishai, the brother of Joab, who was the captain of these 30. Abishai’s story did not rival the story of the three named heroes at the beginning of this section but he was the most renowned of the 30 and became their captain. This was because he killed 300 men with his spear (they kept count…this would have been over some time and not in one battle as with the hero mentioned earlier).

Now we have a third story regarding the 30 who will all be named momentarily. The third one is about Benaiah son of Jehoiada of Kabzeel. He was the captain of David’s bodyguard unit (the Gentiles – Pelethites and Cherethites). He killed a lion (reminding us of David himself) and a mighty Egyptian using the Egyptians own weapon (like David did to Goliath).

Then beginning with verse 24 the text lists the names of the 30 (this does not include the three men named at the start of this section).

The list of the thirty actually names thirty-one. However, the text above said that Benaiah and Abishai were both among the thirty men and they are not listed in the list. Thus thirty is not to be taken too literally – they rounded – but there were thirty something mighty men (perhaps only 30 at a time, with death being a factor esp with Uriah). In fact, the text says at the end of the last verse “thirty-seven in all.” The math is difficult, but if you add the three to 37 you get 40.

Abishai (brother of Joab) the son of Zeruiah is mention in both of the parallel sections. He was one of the giant slayers and one of the thirty (see the story above and not the list).

This is an explicit linking of these two sections.

Then at the center of the chiasm of 2 Sam 21-24 is the “last words” of David (2 Sam 22:1-23:7). These words drawn an obvious parallel to Jacob (Gen 49), Moses (Deut 32-33), Joshua (Joshua 24). Often these farewell speeches were poems (Gen 49, Deut 32-33) and were followed by standard epilogues (Gen 49:28-50:26, Deut 32:44-52, 34:1-12, Joshua 24:29-33). 2 Sam 23:8-24:25 serves as an epilogue of sorts, but it does not mention the traditional epilogue items – for example, we would expect to read of the death of David and his burial. So the comparison is not so much one of literary structure as it is of David to these men.

Even though the structure does not follow the pattern of the books of Torah ((prologue), narrative, poetry, epilogue) what does remain true is that the key to the structure of those books of Torah and now Samuel is the poetry.

If you remember the chiastic structure of the book, an image in an earlier post, one thing that is striking is that the key points of the chiasm — the opening, climax, and closing — are poems.

This final section has two poems. The first one resembles the Psalms – it is a song of deliverance (2 Sam 22). The second one is a prophetic oracle (2 Sam 23:1-7). The first one is also recorded in the Writings as Psalm 18 with some minor differences. It is fitting that this psalm mentioning Saul in the heading would follow David’s deliverance from his Saul-like son Absalom. The structure of the psalm is generally chiastic – the opening and closing praises have similarities, the second and second to last sections deal with deliverances and the center of the psalm with David’s cleanness and righteousness.

The opening and closing of the Psalm highlight the image of God as a rock of refuge. Moses had also spoken of David as a Rock several times in the Deut 32 poem.

In the first section of the psalm about deliverance it is YHWH who is delivering David from his enemies (hence more of the “He” pronoun). The second section builds on this to show David able to defeat his enemies (hence more of the “I” pronoun).

The psalm of David answers in the structure of Samuel to Hannah’s poetic prayer. She had also spoken of God as a rock, had the theme of deliverance or salvation, and mentioned the “anointed” of YHWH. Hannah’s prayer was the promise and David’s psalm was the fulfillment in the structure of the book. There is a sense in which the issues at the beginning of Samuel are now answered by the end of Samuel. It gives the book a sense of being a completed work (which is why splitting Samuel into two is such a problem).

The most difficult section of David’s psalm for us as Christians to understand is the center. How can David be said to be clean and righteous? The answer is that in the context of the covenant with YHWH, David is clean and righteous. David is clean and righteous because YHWH promised to save those who keep covenant. Scripture calls those who keep covenant “blameless” … they were not sinless but forgiven. In the context of the covenant there is forgiveness of sins because of the blood appointed by God. He kept himself from guilt by genuine repentance and sacrifice.

Both the psalm and the oracle call God a rock and David the anointed. 2 Sam 22:51 says, “Great salvation He brings to His king, and shows loyal-love to His anointed, to David and his offspring forever.” 2 Sam 23:1 calls David “the anointed of the God of Jacob” and verse 5 mentions the everlasting covenant God made with David and his house forever. The oracle also fulfills the themes of Hannah’s prayer. She looked for the poor sitting in the dust to be lifted up as king. And David is the son of Jesse who was raised on high.

And a just king (one ruling in the fear of God) is like the sun so that the land may be fruitful. David is that king and yet is a type of the one who is the morning light – like the sun shining on a cloudless morning. Throughout 2 Sam 21-24 there have been hints that David while clean and righteous and the anointed (Hebrew is Messiah) of YHWH falls short of the coming Messiah. This has included mentioning Uriah the Hittite, by telling the story regarding the census, and even in this oracle as it says the king should throw away thorns. David has not done this well – especially considering the thorn who is Joab.

Jesus Christ is the one who is the gardener where Adam had failed – the gardener who dealt with the curse of thorns – the gardener who will weed out the wicked, remove the thorns, and cast them into the fire.

Really the prophetic oracle David spoke is about his Lord Jesus Christ who would be the king to rule justly in the fear of God, dawn on us like the sun and like rain that makes the grass to sprout from the earth, remove the thorns of worthless men, and sit on the throne of David forever.

Thus in the structure of the book poems are included at key places. Hannah’s prayer and David’s psalm and oracle frame the whole of Samuel and David’s lament is found at the center of the book. The poem at the center highlights the central themes of Samuel. It says three times, “How the mighty have fallen!” (2 Sam 1:19b, 25a, 27a). Hannah’s prayer had seen the falling of the mighty and the exaltation of the one in the dust. The lament mentions Saul alone (v.21), then Jonathan and Saul (v.22), then Saul and Jonathan (v.23), then Saul (v.24), then Jonathan (v.25).

The poem personifies their weapons as them – thus the death of Saul and Jonathan is the death of their weapons (v.27). Jonathan had been identified with the bow and Saul with the sword (v.22). The poem contrasts “lest the daughters of the Philistines rejoice, lest the daughters of the uncircumcised exult” (v.20) with “you daughters of Israel, weep over Saul, who clothed you luxuriously in scarlet, who put ornaments of gold on your apparel” (v.24).

It is fitting that a book concerning David would show such diversity in poetic form – a prayer for deliverance, a lament, a psalm of deliverance, and an oracle.

Recent Comments