Ezra-Nehemiah is one book and should be read as one book. The book was probably written around 400 B.C., as suggested in the Dillard-Longman introduction, but they note that it is possible that it was not completed until as late as 300 B.C. In any case, it was not divided into two separate books until much later (after the time of the apostles) and was only divided in Hebrew Bibles beginning in the Middle Ages. Also the titles Ezra and Nehemiah are somewhat misleading as the book is not so much about Ezra or Nehemiah as it is about the community of faith.

The book of Ezra-Nehemiah includes the text of various sources including most notably both Ezra’s and Nehemiah’s memoirs. A memoir, as Dillard-Longman explains it, is different from an autobiography because an autobiographer writes of him or herself in the midst of great events whereas a memoirist writes of the great events that he or she has seen or even participated in them. One thing this invites us to do is to compare the 3rd person narrator with these memoirs to see if Ezra or Nehemiah are being corrected by the narrator.

Noting the shift in the book from third to first person, the introduction tells us that Howard suggests the following basic outline:

”A Historical Review (Ezra 1-6)

Ezra’s Memoirs, Part 1 (Ezra 7-10)

Nehemiah’s Memoir, Part I (Neh. 1-7)

Ezra’s Memoirs, Part 2 (Neh. 8-10)

Nehemiah’s Memoirs, Part 2 (Neh. 11-13).”

Now remember that the memoirs are not about Ezra and Nehemiah, but written by them about the community of faith.

Doug Green notes that the book of Ezra-Nehemiah is a story of building two walls. We might call them Ezra’s wall and Nehemiah’s wall. The former is invisible and the latter is visible. Nehemiah’s wall physically separates the “house of God” from the unclean Gentiles and their world. It was a literal wall. Ezra’s wall spiritually separates Israel from the unclean Gentiles. Here we are speaking of Ezra’s desire for a boundary between the people of Israel and the Gentiles with regard to keeping the law. This means a couple things: one, we will be tracing the themes of these two walls as we progress through the book; two, we are invited to ask the question as to how to apply this book given the way that Jesus has torn down the wall between Jew and Gentile. Ezra-Nehemiah sets the people of God on a trajectory that should help you to understand the situation when Jesus arrives on the scene and to appreciate how much of a challenge the apostle Paul would have as the apostle to the Gentiles from his fellow Jews. Indeed, Green says that the way that the book of Ezra-Nehemiah ends, ”leaves us with more questions than answers. Are these boundaries secure? Will the two worlds remain separate? It is as if ‘To be continued’ has been written at the end of the work, challenging the original readers to make their own story a sequel in which they rise to the occasion and remove all doubts about the security and permanence of the house of God.” But we know too that given the fact that Jesus has torn down the boundary separating Jew and Gentile that we have much thinking to do then about how we apply it.

We also should wrestle with the fact that Ezra-Nehemiah is one of the most boring books of the Hebrew Scriptures. I remember Doug Green saying that he thought that this was intentional. The basic reason as best I can recall is that Ezra-Nehemiah is not the glorious restoration we might envision given the vision of Ezekiel, for example.

Ezekiel 40-42 show us a temple in great detail, “An behold, there was a wall all around the outside of the temple area, and the length of the measuring reed in the man’s hand was six long cubits, each being a cubit and a handbreadth in length” (Ezekiel 40:5). In any case, the picture that unfolds is one of a most glorious temple – a sight to behold – something spectacular. Now to be sure, the genre of those verses in Ezekiel is important – it is a vision and not as if there was the expectation that a temple of such grandeur would ever be actually built.

Then we read this: ”…And all the people shouted a great shout when they praised YHWH, because the foundation of the house of YHWH was laid. But many of the priests and Levites and heads of fathers’ houses, old men who had seen the first house, wept with a loud voice when they saw the foundation of this house being laid…” (Ezra 3:11-12). So the Second Temple was a disappointment to those who had seen the first one. To distinguish these temples we will call the first one the Solomonic Temple or Solomon’s Temple and the second one simply the Second Temple.

The basic point is then that Ezra-Nehemiah is so boring because the people of God were still awaiting the true glorious restoration. In the meantime, they were to await that day by keeping Torah and thus by distinguishing themselves physically and spiritually from the Gentiles. Unlike earlier works among the Writings, the application to today is not so straightforward, since we live in a time also when the prophetic word has ceased and we too are to spend time studying Scripture but we do not keep Torah.

One of the many interesting insights that Doug Green has about this book is how the titular heroes are actually flat characters. As he says, ”Ezra and Nehemiah are uniformly virtuous: Ezra a model of devotion to the Law (Ezra 7:6), Nehemiah equally as noble, with particular emphasis on his care for the welfare of the people (Neh. 1:2-11; 5:1-18). All their actions are consistent with these dominant traits.” Likewise the Gentile opposition to their project are consistently characterized as ”enemies of Judah” (Ezra 4:1) despite their claim to worship YHWH. Now one might be tempted to dismiss this observation simply because the book incorporates a lot of the memoirs of Ezra-Nehemiah. It is not as if the Gentile opposition actually ever is able to speak for themselves and Ezra and Nehemiah portray themselves in a positive light. We only know the opinion of Ezra and Nehemiah as to the motives of their opponents. As Green puts it, ”Narrating a story from the perspective of one side of a conflict inevitably results in a black-and-white portrayal of the combatants.” But what this characterization allows the book to do is to move us from focusing on the charismatic individual to the community of faith. Ezra-Nehemiah does this by describing the community of faith as somewhere between these characterizations of Ezra and Nehemiah, on the one hand, and the Gentile opposition, on the other hand. Simply put: Ezra and Nehemiah are good, the Gentile opposition is evil, and the community of faith is somewhere in between these extremes. Therefore, what matters most to the story is the community. Thus the question as we read is whether the people will choose to be righteous or evil. Although, Green notes that Ezra 9:1 mixes this by describing the people as ”the people of Israel” and by saying that they are like the Canaanites. Again the issue is that the people are not wholly righteous nor are they wholly evil in their actions like the flat leaders on both sides. Therefore Green can say, ”success or failure in building the ‘house of God’ depends less on Ezra and Nehemiah or their enemies and more on the people.”

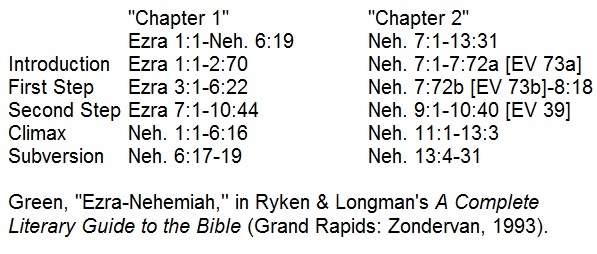

I find Green’s outline of the book most incredibly helpful. He suggests that there are two ”chapters” to the book. The first is Ezra 1:1-Nehemiah 6:19 and the second is Nehemiah 7:1-13:31. Moreover, each chapter follows the same outline: Introduction, First Step, Second Step, Climax, Subversion. The two halves also correspond to the two major themes. The major theme of the first half is the building of a literal wall. The major theme of the second half is the building of the figurative wall.

He suggests the following divisions:

Such an outline reinforces the unity of Ezra-Nehemiah. Ezra simply does not stand alone as a book from Nehemiah – the two are one larger work.

The other issue of introduction with regard to Ezra-Nehemiah that we will address now is its relationship to Chronicles. Chronicles also is a single book. Some have suggested that Chronicles and Ezra-Nehemiah should be considered one work, but lately the consensus has been that they have different human authors. The reason that these two books are read together is the way that the one borrows from the other.

Chronicles ends this way: ”Now in the first year of Cyrus king of Persia, that the word of YHWH by the mouth of Jeremiah might be fulfilled, YHWH stirred up the spirit of Cyrus king of Persia, so that he made a proclamation throughout all his kingdom and also put it in writing: ‘Thus says Cyrus king of Persia, ‘YHWH, the God of heaven, has given me all the kingdoms of the earth, and He has charged me to build Him a house at Jerusalem, which is in Judah. Whoever is among you of all His people, may YHWH his God be with him. Let him go up”” (2 Chron 36:22-23).

Ezra-Nehemiah begins this way: ”In the first year of Cyrus king of Persia, that the word of YHWH by the mouth of Jeremiah might be fulfilled, YHWH stirred up the spirit of Cyrus king of Persia, so that he made a proclamation throughout all his kingdom and also put it in writing: ‘Thus says Cyrus king of Persia: YHWH, the God of heaven, has given me all the kingdoms of the earth, and He has charged me to build Him a house at Jersualem, which is in Judah. Whoever is among you of all His people, may his God be with him, and let him go up to Jersualem….”’ (Ezra 1:1-3a).

Now whichever of these books is first has clearly borrowed the language of the other. The most interesting thing then is how the Hebrew Scriptures reverse the order of the books. Rather than having Chronicles first and Ezra-Nehemiah second, such that the beginning and end of these two books are together, they put Ezra-Nehemiah first and Chronicles second. The result of this is that the reader of the Hebrew Scriptures understands that his position is that of someone living in the days of Ezra-Nehemiah. In other words, he or she is waiting for the glorious restoration of Israel.

Recent Comments