We are going to begin this article with an overview of the speeches found in the book of Job and then begin to look specifically at the first speech. Job 3-37, covering most of the book, are speeches by Job and his three friends plus one:

Job’s Lament (Job 3)

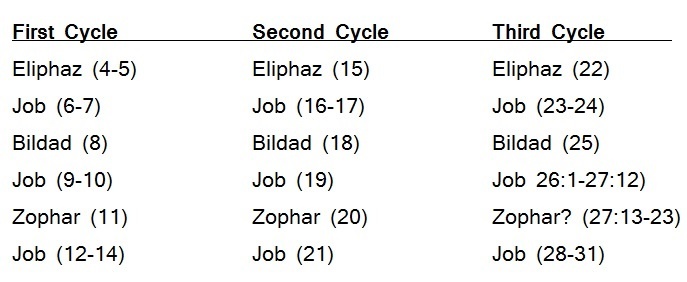

Three Cycles of Dialogues (Job 4-27)

Poem on Divine Wisdom (Job 28)

Job’s Summary & Final Defense (Job 29-31)

Elihu’s monologue (Job 32-37)

The poetic speeches begin with a monologue in the form of a lament. It shares the structure and feel of the personal laments in the Book of Psalms. The poetic speeches then continue with three cycles of dialogue. Most people then and today do not carry on normal conversation in poetry. But these speeches are highly stylized and the friends follow the same order: Eliphaz, Bildad, Zophar with Job responding to each.

The Dillard-Longman introduction gives us this chart:

The speeches of Job’s friends get considerably shorter by the third cycle. The Dillard-Longman introduction explains it as ”reflecting the fact that the three are, we might say, running out of steam.” ”In this way, the dialogue communicates that the three friends ran out of arguments against Job. This literary device leads nicely to the speech of the frustrated Elihu (chaps. 32-37)” (p.203).

The book of Job is wisdom literature inviting us to ponder who has the right insight into the reasoning for Job’s suffering. The three friends espouse ”retribution theology.” The idea is simple: God blesses the righteous and God curses the wicked. Since Job appears cursed, he must be wicked. Job responds to this reasoning not by claiming to be sinless (cf. Job 9:2) but rather by denying that is why he is suffering and questioning whether God will give him justice.

Job’s Lamentation

Before the poetic lament there is a subtitle that simply says, ”After this, Job opened his mouth and cursed his day. And Job said,” ”His day” has been taken to mean the day of his birth given Job 3:3. Aside from having that verse we would have assumed that he meant that he was going to curse his fate – so to speak. The introduction likely means more the latter than the former – his lamentation laments both his ever existing and the suffering he is currently experiencing.

The lament of Job is threefold: First, he laments his birth/conception; Second, he laments that he did not die in his mother’s womb or right after birth; and Third, he laments that those who suffer do not get to die quickly. David R. Jackson is quick to point out that suicide is not even on the table as an option. Instead, Job is lamenting that he has to live with this great suffering.

Regarding the first part of the lament note how it moves backwards in time from the day of his birth to the night of his conception. Things are so bad for him at the present that he wished that his life had never begun. Of course, while birth is important he understands that life begins at conception. This is a demonstration of poetic parallelism. It is not that both lines are saying the same thing twice but that the second line takes the first one more step forward (or in this case, backward).

Job seeks retroactively to have the day cursed using all kinds of terminology for darkness. We do not have nearly as many words for darkness in English, which causes the translators to stumble around for ways to render verses 4-6. His real complaint is not with his birthday (nor for that matter with the day of his conception) as much as he might call for those days to be cursed on the calendar. But we understand what he means pretty easily.

Job also creatively applies ancient myths like that regarding Leviathan (cf. Job 3:8) to describe what he is saying. He shows no hesitation in doing so. He is not endorsing those myths by doing so, rather he is simply borrowing them to make his point.

In the second part he begins, ”Why did I not die at birth, come out from the womb and expire?” (Job 3:11). In this section Job also moves backwards to an earlier time than birth at a full-term. The picture of a miscarriage is clear in verse 16. It says, ”Or why was I not as a hidden stillborn child, as infants who never see the light?”

The third part of the lament begins with verse 20. It is here where we finally get to the heart of his lament. Job is crying out because those who suffer have to live with it for so long. Those ”who long for death, but it comes not, and dig for it more than for hidden treasures, who rejoice exceedingly and are glad when they find the grave…” (Job 3:21-22).

Recent Comments