English Bibles place Ruth after Judges and right before 1 Samuel. As a historical sequence this makes some sense given that Ruth is set in the time of the judges (Ruth 1:1) and it then can serve as a brief introduction to the book of Samuel (assuming that you understand that Samuel is one book, especially since Ruth ends with a genealogy leading to King David). Reading the book here can offer many insights. In the Hebrew Scriptures, however, the book of Ruth falls after Proverbs and before Song of Songs. This actually can make a considerable difference in how we even approach reading the book.

Placing Ruth right after Proverbs highlights the connection between the concluding poem of Proverbs and the person of Ruth. The poem concerns a “worthy woman” (Pro 31:10) And Boaz said to Ruth, ”And now, my daughter, do not fear. I will do for you all that you ask, for all my fellow townsmen know that you are a worthy woman” (Ruth 3:11). The phrases I would render “worthy woman” in these two passages are identical in Hebrew, but Proverbs 31:10 is translated into English in a variety of ways.

Ruth is one of the heroines of the Hebrew Writings. The other heroines are the woman of the Song of Songs, which is the next book, and Esther who falls in the parallel spot to Ruth in the chiastic structure of the Writings.

As one of the Writings, which begin with the Psalms, it is not surprising then that Ruth had a liturgical purpose. Perhaps it is meant to be understood as a liturgy in light of the topic of fertility. It is the first of the Megilloth (Hebrew for scrolls), which were read at the following feasts: Ruth at Weeks (aka Pentecost), Song of Songs at Passover, Qoheleth at Tabernacles, Lamentations on the 9th of Ab, and Esther at Purim. We do not know when they began to be read at these feasts, but we suspect it was during the 2nd Temple. Reading Ruth on Pentecost is appropriate given how Pentecost was a celebration of the harvest and the book of Ruth opens during a famine, but then chapters 2 and 3 concern a harvest. The link between a harvest and the birth of children is fairly obvious in ANE culture. Reading the book liturgically — as an exercise of worship — changes how we “understand” it.

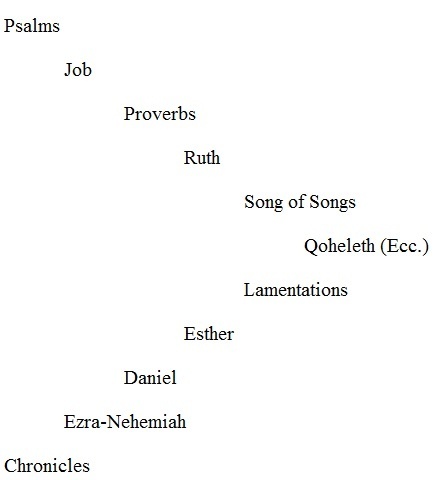

(Note that the Writings read at these feasts are not arranged in canonical order by the calendar order of the feast (i.e. Passover is before Pentecost and the 9th of Ab is before Tabernacles). Nevertheless, remember that there are three major groups among the Writings: Psalms, Job and Proverbs; the Megilloth; and Daniel, Ezra-Nehemiah, and Chronicles.)

Additionally, note the international outlook of the Writings. Job was not an Israelite, though he can serve as a parable for Israel. Proverbs contains wisdom written by Gentiles at key places – i.e. The third and fourth collections borrowed from the Gentiles and brought the Proverbs of Solomon to a close, the sixth and seventh collections were apparently written by Gentile believers. Ruth was a Moabitess (more about this momentarily). Esther was the Queen of a Gentile nation. Daniel served in Gentile nations.

The point that Ruth was a Moabitess was made repeatedly – Ruth 1:22, 2:2, 2:21, 4:5, 4:10, cf. also Ruth 1:4 and 2:6. Why is it important that Ruth was a Moabite? ”No Ammonite or Moabite may enter the assembly of YHWH. Even to the 10th generation, none of them may enter the assembly of YHWH forever, because they did not meet you with bread and with water on the way, when you came out of Egypt, and because they hired against you Balaam the son of Beor from Pethor of Mesopotamia, to curse you. But YHWH your God would not listen to Balaam; instead YHWH your God turned the curse into a blessing….” (Deut 23:3-5, cf. Nehemiah 13:1ff). The 10th generation was a poetic way of saying forever. Note the parallelism of the phrases: ”No Ammonite or Moabite may enter the assembly of YHWH even to the 10th generation // none of them may enter the assembly of YHWH forever.” After all, the number 10 means fullness – even to the fullness of their generations. Remember that the Ammonites and Moabites are fairly closely related to Israel – these were the descendants of Abram’s nephew Lot. Thus the problem is that not only did they refuse to show hospitality to Israel, but worse than this they failed to show hospitality to their own kin.

Then note the genealogy that concludes the book and the title has the feel of a Genesis genealogy: ”Now these are the generations of Perez: Perez fathered Hezron, Hezron fathered Ram, Ram fathered Amminadab, Amminadab fathered Nahshon, Nahshon fathered Salmon, Salmon fathered Boaz, Boaz fathered Obed, Obed fathered Jesse, and Jesse fathered David.” The key is to count: Boaz is 7th and David is 10th. Boaz is 7th like Enoch (Gen 5:24). And David is 10th like Noah (Gen 5:29) and Abram (Gen 11:26).

Note the shady associations in this genealogy. Judah’s line was to have the king of Israel (Gen 49:10. However, we read in Genesis that Judah slept with his widowed daughter-in-law Tamar, a forbidden union, and fathered twins Perez and Zerah. Note then too Deuteronomy 23:2 reads, ”No one born of a forbidden union may enter the assembly of YHWH even to the 10th generation, none of his descendants may enter the assembly of YHWH.” David is the 10th generation. The genealogy, as is likely the case also with those in Genesis, skips generations.

The elders at the gate make a couple of Scripture allusions. The first is: ”May YHWH make the woman, who is coming into your house, like Rachel and Leah, who together built up the house of Israel” (Ruth 4:11). This is during the chaos of the Judges and their prayer is that Ruth would rebuild the nation of Israel through childbearing. This is exactly what she did as the child that she bears becomes the grandfather of King David. The second is: ”May your house be like the house of Perez, whom Tamar bore to Judah, because of the offspring that YHWH will give you by this young woman” (Ruth 4:12). Perez is the ancestor of Boaz. Note that in this context is the first time Boaz calls his wife-to-be ”Ruth the Moabitess.” Hence there are allusions both to Lot and Judah.

You probably remember the story of Lot with regard to Sodom here are some details important for us here: Lot’s daughters were engaged to get married, but their husbands did not flee with Lot because of their unbelief. Lot’s wife looked back and turned into a pillar of salt. Thus Lot had no male heirs, no wife to have children, and worse he moved with his daughters into a cave (Gen 19:30). In this context then the daughters got Lot drunk and slept with him and the eldest daughter gave birth to Moab. Remember that Ruth is a descendant then of Lot and Moab.

A similar series of events took place concerning Judah who married a Canaanite had wicked sons that YHWH killed. Tamar should have married the third son (a Levirate marriage like that done in the book of Ruth) but Judah was not going to let that happen. In this context then Tamar dressed up as a prostitute and slept with Judah.

Lot, Judah, and Elimelech all separated themselves from the community of faith with tragic consequences – foremost among the consequences being that all their female children and daughter’s-in-law are left without men available to redeem them, in each a kinsman steps in or is forced to do so, and all three have a bed-trick during celebrations. However, Ruth and Boaz did not repeat the mistakes of their ancestors Lot and Judah. There was no sin involved in this latest bed-trick.

Also important to the ending of the story is what I like to call Boaz & Mr. So & So (though I am not the first to call him this). The name of Boaz will never be forgotten. But notice that in Ruth 4 the author avoids telling us the name of someone who was a closer redeemer than Boaz because he gave up that right to redeem and let it pass to Boaz. Ruth 4:1 in the ESV calls this other kinsman redeemer who did not redeem, ”friend.” But the Hebrew is closer to saying, ”Mr. So & So.” We do not know who this person was, but everyone knows who Boaz is – the ancestor of King David!

I want to end looking at Ruth by going back to the beginning of the story and making some important observations: The first chapter also makes excellent use of contrasts. One such contrast is that between Bethlehem and Moab. Bethlehem is Hebrew for ”house of bread.” Moab was the nation (their own relatives!) who refused to give bread to the people of Israel when they came out of Egypt. They had failed to show hospitality to Israel – which is a grave sin in the ANE.

The theme of Judges is, “In those days there was no king in Israel. Everyone did what was right in his own eyes” (cf. Judges 17:6, 21:25). Elimelech’s name is Hebrew for “My God is King.” But he did what was right in his own eyes and did not trust in the providential care of God for relief from the famine in Bethlehem. Thankfully, in spite of their decision to go to Moab, YHWH gave them bread to eat.

A second major contrast is between Ruth and Orpha. Both were devoted wives to their husbands, which we can see because both remained to take care of their mother-in-law. Orpah even went with Naomi and Ruth on the way to Judah. The text tells us, “So she set out from the place where she was with her two daughters-in-law, and they went on the way to return to the land of Judah” (Ruth 1:7). But Naomi challenges her daughters-in-law (for whatever reason – her motives are not necessarily clear).

The first time she tells them to return home both tell her, “No, we will return with you to your people” (1:10). But when Naomi challenges their commitment again by noting that there is no guarantee and it is rather unlikely that they will have a new husband and children, Orpha kissed her mother-in-law goodbye. Thus Orpha was not willing to give up everything – including her family and the potential for remarriage in Moab – in order to follow Naomi to Bethlehem. But while Orpha kissed her mother-in-law, Ruth clung to her (Ruth 1:14). This is the language of marriage from Genesis 2:24 of cleaving (same Hebrew word). Ruth was showing that she wanted to be the bride of the Redeemer God by clinging to Naomi.

And Naomi challenged her again, to which Ruth responded in a way that it was clear that she would not be turning back. “Do not urge me to leave you or to return from following you. For where you go I will go, and where you lodge I will lodge. Your people shall be my people, and your God my God. Where you die I will die, and there will I be buried. May the Lord do so to me and more also if anything but death parts me from you” (Ruth 1:16-17). Notice the increasing intensity of her dedication with each line. The last line is a self-imprecation (calling the curse of God upon herself if she should do otherwise).

The other major contrast of characters is that of Naomi and Ruth. Just as Elimelech, Naomi’s husband, had earlier been acting the opposite of his name “My God is King,” so too Naomi was acting the opposite of her name. Naomi means pleasant and yet Naomi was bitter and she tells the people of Bethlehem to call her Mara, which is Hebrew for bitter. Her statement of faith is not as resounding as Ruth. She says, “I went away full, and the Lord has brought me back empty” (Ruth 1:21).

We remember that she went away during a famine rather than full, so this is a kind of odd thing to say. Really it is an acknowledgment that she has hit bottom. Like the Prodigal Son off in the foreign land who comes to his senses, she has come to her senses. But she also is like the Prodigal Son in not seeing that the Father wants His children to return not to be His slaves but to be His children. She knows that God is in control, but she does not appear to be convinced that He is working everything together for her good. Instead, she says just the opposite, “Why call me Naomi, when the Lord has testified against me and the Almighty has brought calamity upon me?” I am not worthy to be called your Daughter, she is saying to God. And I anticipate that the future will only be more heartache rather than blessing because you have been pouring out your curse upon me.

Ultimately, Naomi was a type of Israel who would come to Christ and Ruth was a type of the Gentiles who would come to Christ. Naomi’s attitude would change, but it took some time. And Boaz is the Christ-figure of the story. He is a type of the coming Christ – a kinsman redeemer. Boaz imitates YHWH – he takes Ruth under his wings (Ruth 2:12). And Boaz redeems Ruth and thus Naomi and Elimelech.

For more insights and reflections on the book of Ruth, especially application to your life today, be sure to check out my four sermons on the book back in 2010.

Recent Comments